There are many styles of leadership, and while there are standards and best practices, our own personal style is determined by the unique experiences we have throughout our lives.

The person I am today is shaped by the career I had as a scientist before making the leap from academia to the tech industry nearly 8 years ago. I thought I would let you all humor me as I take a trip down memory lane and talk a little bit about what it was like working on the ATLAS Experiment at CERN, a particle physics laboratory located near Geneva, Switzerland.

ATLAS’s claim to fame, along with our sister/frenemy experiment CMS, was the discovery of the Higgs Boson, a never-before-seen particle hypothesized to exist through the theoretical framework known as the Standard Model of Particle Physics. In fact, CERN just recently celebrated the 10 year anniversary of the joint ATLAS/CMS discovery, which was announced on July 4, 2012.

Getting from data collection to statistical analysis to the discovery of the Higgs Boson took an unimaginable coordination effort, spread across time zones with physicists working around the clock at over 170 institutions in 38 countries.1 To put it in perspective, ATLAS was processing the remnants of bunches of protons colliding with each other every 25 nano-seconds, and saving roughly 320 MB per second of raw event data. Now those were some event logs. Data collection, quality control, curation and analysis required to discover a brand new particle with 5 sigma significance really took a whole village. The paper published by the ATLAS collaboration that details the analysis has nearly 3000 authors, and I was lucky to be one of them.

In case you’re immediately wondering whether 3000 authors still seems like a lot for one paper, you’re not alone. It’s not even common within other academic disciplines for a paper to have any more than a dozen authors or so,2 and even less common for the scientist who actually led the analysis not to be at the top of the list (or “first author”). But in particle physics, no matter how directly a scientist was involved on a particular analysis, every qualifying collaborator was an author, and the list was always presented alphabetically. On ATLAS, that meant every paper was cited as G. Aad et al (no joke).

As much as this system may appear to incentivize physicists to sit back and claim results they didn’t contribute to, authorship on ATLAS wasn’t just handed out. When I joined the ATLAS collaboration in 2006, fresh out of the more structured environment of graduate-level classwork, the accepted cultural norm was that people like me didn’t deserve to be an author yet. Any new scientist joining the experiment was required to go through a minimum one-year period of non-physics-analysis work called their “authorship qualification,” where qualifying tasks included things like writing simulation software, contributing to data acquisition systems, taking measurements to calibrate the machine (we called this detector performance work), measuring and discarding outlier particle collisions that didn’t meet our data quality criteria, and actually building and commissioning the detector hardware itself. This was taken very seriously, with no exceptions.3

I’m not necessarily advocating that the data community adopt some kind of equivalent “qualification” formalism, but one thing authorship qualification did ensure in particle physics research, and what I still see as a gap in the tech industry, was that every scientist was given an opportunity (or forced to gain) a deep appreciation for at least some small part of the incredibly complicated upstream data collection process. It also meant culturally that data platform-related work was more revered in the organization, while those who just checked the minimum-required qualification box and never internalized that data acquisition appreciation were sort of frowned upon. Not that some physicists didn’t still try for analysis glory above all else, but success in particle physics depended highly on reputation, which tended to weed out the posers.

I see kind of the opposite in industry. Data Scientists hold the spotlight and are revered, and are financially compensated far more than their upstream data colleagues. Companies don’t always structure their data teams together, and when they do, interactions between scientists and other data platform practitioners are often tepid, with “just write us a ticket,” throw-it-over-the-fence style exchanges. What if we started acknowledging all contributions and created an intentional culture for the entirety of the internal “analysis collaboration?” And not just limited to the people we think of today when we hear the term “data practitioners” but really everyone who creates or touches the data needed to make an analysis successful. With that lens, I would also include other groups not traditionally thought of as part of a data team, such as software engineers responsible for event instrumentation and IT teams responsible for 3rd party tools and integration as equal members of this internal data collaboration.

There is something about the fact that there is a distance between different crafts, including the work of analysts, data engineers, dev ops, and software engineering, that causes unnecessary inefficiencies in a full stack data program. A plethora of new startups have attempted to solve data customer issues like bad data quality, inconsistent telemetry, poor data discoverability/lineage, etc. by throwing more and more tools on the market. But we’re still kind of missing the people aspect of the problem. Why would a software engineer ever be excited about getting instrumentation right if they never see the downstream business impact of the telemetry they added to product features?

Instead, what issues would disappear if we structured ourselves in such a way so that everyone involved, no matter how remotely, felt like an “author” of every data analysis? One way to achieve this is to improve communication about impact and share positive feedback consistently back to the more distanced data practitioners as equal supporters of analyses, and to always remember to give them credit when presenting results. To take it one step further, data leaders with moderate-sized teams could think about setting up a system of rotations between different groups. Where flexibility allows, we can create opportunities for more junior data scientists to spend 3-6 months on a data engineering team, or have a front-end engineer responsible for instrumenting events spend some time answering ad hoc product manager data requests on the analytics team.

As for the scientists on ATLAS who headed over to the tech industry, some eventually gravitated toward software engineering, some toward analytics, some toward research on machine learning topics. Somehow I ended up writing blog posts about how we can all work better together.

Personal Note

I know it’s been a while since I last wrote a post, which up until June I was trying to do on a bi-weekly cadence. Consistently publishing is still my goal, and while I wanted to hold myself accountable to that even as I started my new role (like how David Jayatillake did, #impressed), I will admit that writing for this blog went on the back burner during my initial ramp up time.

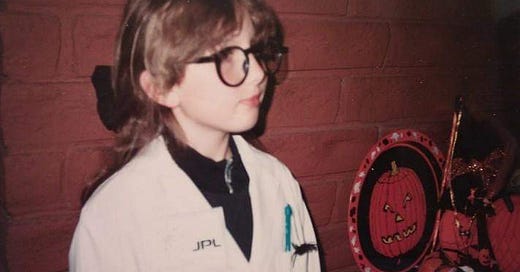

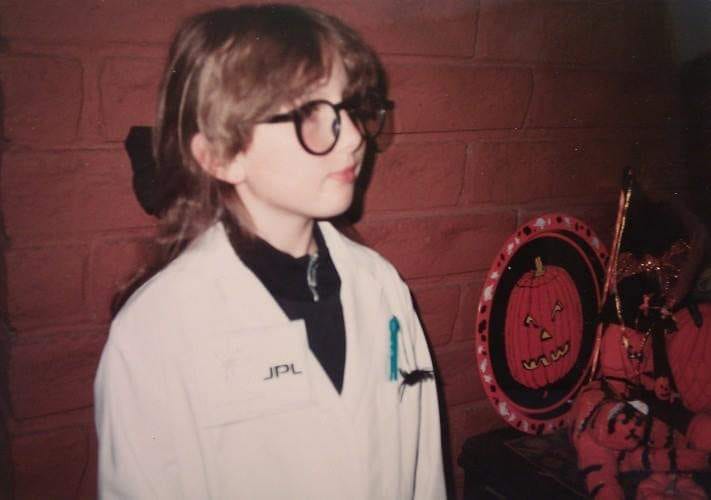

Then, just as I was feeling settled into a new routine and starting to get inspired to write again, my world got flipped upside down when my mom unexpectedly passed away. I’m still coming to terms with what that means, and I don’t have all the words yet. But since this blog touches on factors that influenced the person I am today, I can’t circumvent honoring her memory here.

I didn’t come from a family of university graduates, but my mom was a life-long learner. She had hundreds of books in every room of the house, and had read them all. She cared deeply about the natural world, and introduced me to science advocates like Carl Sagan and David Attenborough when I was still very young. She volunteered at a youth science program where I attended summer classes, further encouraging me down the path of the person I would become. Her attitude towards learning rubbed off on me, and I still aspire to care as deeply as she did about people and this planet. She pushed me to keep going in school, bragged about me to her friends when I was at CERN, and maybe even questioned my choice to enter the tech world a little. She was also the number one fan of this blog.

Everyone brings pieces of who they are, and who they were, every day they show up at work. Truly the things that make us unique also empower us to bring new ideas and points of view to the table, and there is value from all of it. There is no wrong way to find your career path, other than to try to be someone you’re not. For me personally, I’ll always be a scientist, and no matter what my job is, I know that would make my mom proud.

Correction: when I first published this I said “over 125 countries.” Definitely not that many, but still a lot.

The joint ATLAS/CMS Higgs discovery paper broke some kind of academic authorship record and apparently, scientists minds.

Snippet from the ATLAS Authorship Qualification criteria, including original emphasis formatting:

“Have spent at least 80 working days doing pre-agreed ATLAS technical work, where ‘80 working days’ does not mean ‘part time for a couple of months’ or ‘did something related to it on about 80 different days.’ It means that over the course of a year, the person should have spent a bare minimum of 80 eight-hour working days entirely on the specific topic agreed to with the project leader or activity coordinator.”

They go on to say:

“If you spend more time on your physics analysis than you do on your qualification task during the qualification year, you are not taking the qualification work seriously enough!”